The climate and ecological crises must be tackled together. The potential for the agricultural and food sector to mitigate these crises is huge but also overlooked and understudied. A recent Nature publication provides insight into how the agriculture and food sectors could contribute to the targets set by the Paris Agreement.

Samantha Ibbott reports.

The latest IPCC report made it abundantly clear, with our current mitigation laws and policies it is likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century, making it harder to keep rising global temperatures below 2°C. Globally, the agri-food system is estimated to be responsible for a third of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and is also the main driver of species and habitat loss in the EU. This must change.

A societal shift

The European Green Deal is designed to shift Europe’s economy and society to a sustainable and climate-neutral one by 2050. This will require an unprecedented level of action across all sectors – including the agriculture and food sectors.

On the climate front, the European Union recently adopted two revised regulations, as part of the Fit for 55 package, with the aim of ensuring that the EU reaches its target of reducing net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030.

The first is the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), which requires the agriculture, building, transport, waste, and small industries sectors to jointly cut their emissions by 40% by 2030. The second is the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation, which governs related land use emissions and has set a new target of 310 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2eq) of net removals in that sector in 2030. If achieved the EU would increase its carbon sink by 20%.

To deliver on these new and binding targets, EU countries will now need to design policies to support actual change on the ground and they must do so through two key processes. First, each country is required to submit an updated draft of their National Energy and Climate Plan (NECPs) by June 2023 to reflect the increased 2030 targets.

Europe’s agricultural sector is a huge emitter, yet it was essentially ignored in the first NECPs (published in 2019) and emissions from the fertiliser and livestock sectors – two of the largest sources of agricultural GHG emissions – were left largely untouched. If nothing changes then the sector is only expected to reduce emissions by a mere 1.5% between 2020 and 2040 – hardly a fair contribution.

A change in appetite

To take these targets seriously, it is crucial that EU countries take a hard look at their agri-food emissions and put forward concrete measures in their revised NECPs. This is a vital step, but it’s not enough on its own. The second process unfolding this year is arguably even more critical, due to its gigantic budget: the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The CAP regulation requires EU countries to assess and potentially adjust their CAP Strategic Plan (national-level plans designed to implement the CAP) to remain consistent with revised legislation – in this case the LULUCF and ESR – within 6 months of its entry into force. With these two laws entering into effect, on 11 May 2023 and 16 May 2023 respectively, the countdown begins. We recommend reading Arc2020’ recent article on amending the CAP Strategic Plans to learn more.

As our most recent assessment has highlighted, the current CAP Strategic Plans fall short on climate mitigation and will not trigger the large-scale transformation needed for the agriculture sector to respond to the scale and urgency of the climate and biodiversity crises. This is why it is necessary to make sure that EU governments step up their game and strengthen their current NECPs and CAP Strategic Plan.

We must do more, and we must act now. The agricultural sector can and should play a role in climate adaptation and mitigation, ecosystem restoration and protection, and the safeguarding of human health. But what farming practices would be most effective and should be incentivised by the CAP?

We need to change, but how?

In 2021, we collaborated with researchers from Imperial College London (UK) to develop an “agroecology” scenario for the transformation of agriculture and diets, which they then integrated into an interactive model, called ARISE (AgRIculture and food SystEm). Following the publication of the preliminary results – an “EEB pathway” for a net-zero agricultural sector – the researchers refined the model further for a UK scenario. They recently published the results in Nature, a prestigious scientific journal.

The agroecological EEB pathway in the ARISE model allows users to identify the benefits and trade-offs of a transition to agroecology and compare these results to other scenarios – such as the widely popularised ‘sustainable intensification’ scenario, which is heavily promoted by farm and Agri-Chemical industries and currently dominates the literature.

The scenario developed by the model and EEB pathway assumes that meat consumption and food waste is halved, that dairy intake is cut by 45%, and that there is self-sufficiency for feed and no increase in food imports. It also assumes full adoption of agroecology, which would involve the phasing out of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, and the re-integration of biodiversity-rich areas on farmland, through hedges and the large-scale adoption of agroforestry, among other things.

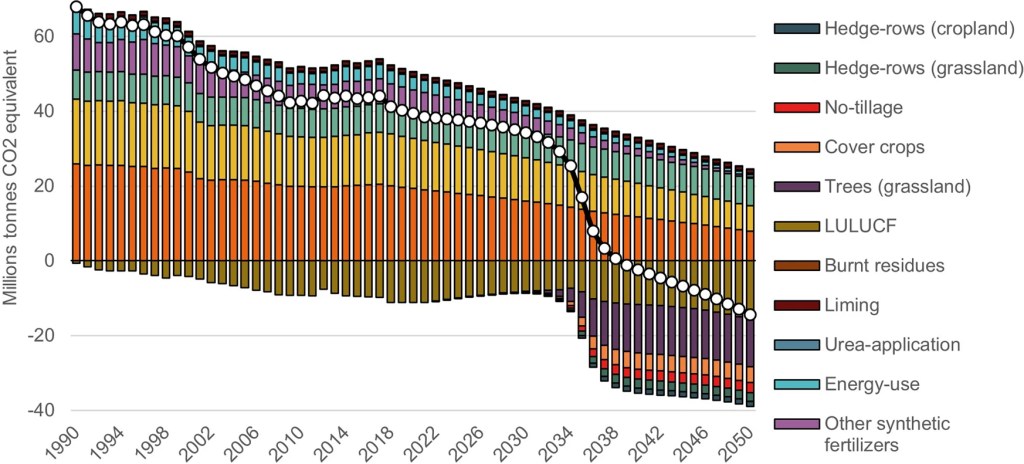

The results? If the EEB pathway was implemented in the UK then, by 2050, there would be a 60 MtCO2eq reduction in agricultural emissions compared with 2017 emissions. This makes agroecology an entirely credible climate change mitigation pathway for agriculture, given the right behavioural changes. Especially when compared with other pathways, including the Climate Change Committee pathways, excluding the BECCS, (-50 to -80 MtCO2e) and the Centre for Alternative Technology (-72 MtCO2eq).

Mind the gap

Without nature restoration and protection we cannot achieve climate targets, yet sustainable intensification – which fails to grasp this approach – dominates the carbon farming debate and, moreover, has also become a buzzword in the whole agricultural policy discussion. Focusing solely on efficiency improvements misses the bigger picture and risks agricultural resilience.

Furthermore, sustainable intensification scenarios tend to be based on extremely optimistic projections for yields, despite the fact that yields have stagnated in the EU for the last decade and are coming under increasing pressure from climate change and biodiversity loss.

Agroecology on the other hand applies “ecological concepts and principles to optimise interactions between plants, animals, humans and the environment” (as defined by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organisation, the FAO). As studies into sustainable intensification far outweigh those on agroecology, research like this provides policymakers with valuable insights into various scenarios, allowing for more informed decision-making.

The basis of resilience

Healthy ecosystems are the basis of a resilient agricultural system, especially in a changing climate. Producing food in harmony with nature, rather than against it, would benefit society and the natural world.

While sustainable intensification strives to force agricultural land to do more with less – whilst making space for nature and carbon sequestration elsewhere – agroecology brings nature back to the farmland and seeks to limit agricultural emissions and increase carbon sequestration on agricultural land by restoring healthy soils and diverse landscapes that include hedges and trees. Such actions have the potential to sequester 150 MtCO2e by 2050, increase the resilience of farms, and benefit environmental and human wellbeing by phasing out synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

In addition to the phasing out of synthetic inputs, agroecology is a step away from the industrial rearing of animals and a step towards extensive and mixed farming. This reconnects animals with the land, allowing them to fulfil their role as megafauna shaping the landscape, increasing biodiversity and nutrient recycling, among other things.

And finally, measures such as agroforestry (integrating trees and shrubs into agricultural landscapes) and the rewetting of peatlands, that were drained for agricultural use, hold huge potential for climate mitigation and adaptation. It really is a win-win-win scenario.

We don’t need another techno-fix

While it has become clear that technological innovation is only a small piece of the puzzle, the EU’s agricultural lobby and big agribusinesses don’t seem to tire of promoting sustainable intensification as a silver bullet for all our problems.

Techno-fixes such as methane-suppressing feed additives are dominating the debate around how to tackle the sector’s giant methane problem, even though the science is clear: we need to reduce livestock numbers and move towards more plant-based diets to truly deliver emissions reductions.

On top of this, a shift in diet would address the other issues related to the intensive rearing of livestock, such as their reliance on imported feed, animal welfare concerns, and air and water pollution.

As the EU grapples with how to achieve the necessary GHG emissions cuts to meet its commitment to the Paris Agreement, tools such as ARISE provide a means for exploring critical trade-offs, supporting understanding and decision-making. This analysis provides valuable insight into the untapped potential of GHG mitigation pathways in agriculture and the possibility of bringing nature back to farmland through agroecology.

With a high level of ambition, a shift in social behaviour (such as dietary patterns), a reduction in food waste and an improvement in agricultural practices, the agriculture and food sector could play a significant role in reaching the targets of the Paris Agreement.

But we must pick the right path.