The European Commission continues to describe the Common Agricultural Policy as “ambitious”, yet its own evaluation of the CAP’s impact reveals that the farm subsidy scheme is inflicting massive damage on Europe’s biodiversity, water resources and nature.

In this in-depth feature, Célia Nyssens explains why the CAP is not fit for purpose and outlines how it can be reformed.

On Friday 27 March 2020, the European Commission snuck out two much-awaited reports: official evaluations of the impact of the EU’s largest subsidy scheme, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), on our biodiversity and on our water. Given the ongoing reform of that very same policy, the forthcoming Farm to Fork Strategy, which aims to make food production more sustainable, and the upcoming Biodiversity Strategy, it is vital that policymakers and stakeholders alike receive timely, accurate and detailed information on the CAP’s environmental performance.

The Commission has tried to put a positive spin on the reports’ findings but the EEB’s assessment of the documents tells a very different story. In this article, I will take you through the real takeaways from these reports.

1. The state of our wildlife, natural ecosystems, and precious water is deteriorating

- Farmland birds populations have declined by 32% since 1990

- Butterflies who live in grasslands have declined by 39% since 1990

- Aquatic biodiversity is in decline due to pressures from agriculture among others

- Around halfof EU rivers, lakes and coastal waters do not meet legal quality requirements and, in most EU countries, this is because of pollution from agriculture

- Water quality is the lowest in the parts of the EU where agriculture is most intensive: in Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, for example, 92% of the surface water is substandard

- Agriculture is the second largest user of water, with 12 EU countries reporting that farming is putting a lot of pressure on their surface water resources

2. The reports findings are not news to experts in the field. Many scientists have long been criticising the CAP, drawing on a mountain of evidence that was already out there

A recent statement signed by 3,600 scientists did not leave room for misunderstanding: “The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is failing with respect to biodiversity, climate, soil, land degradation as well as socio-economic challenges.”

In 2017, the EEB and BirdLife Europe published a thorough evidence-based assessment of the CAP carried out by leading CAP scientists and reviewed by experts. The assessment was unequivocal: “Current trends and CAP’s performance indicate that sustainability, along the axes of social, ecological and environmental dimensions, has not been achieved and is unlikely to be achieved under current conditions. The CAP does not adequately address the most relevant SDGs associated with it.”

3. Despite the mounting evidence, the Commission continues to defend the CAP

The press release that accompanied the reports stated that the “CAP increases [the] ambition of member states on the protection of biodiversity, and raises awareness on water issues.” Now of course, if you start from a very low baseline, it’s easy to increase some ambition and raise some awareness, but this does not mean the EU is achieving anything, especially given the urgency of the environmental crises we are facing and the ambitions outlined in the European Green Deal.

4. Is “cross-compliance” protecting the environment? The evidence is mixed.

Cross-compliance sets the basic rules that stop environmentally harmful farming practices, which most farmers must respect to receive CAP subsidies. These are rules such as ‘you need to comply with authorisation procedures in order to abstract water for irrigation’ or ‘don’t plough in the direction of the slope to avoid soil erosion’. Simple, but really important.

Despite how basic most of those rules are, the scientists doing the evaluation studies struggled to find “evidence of their actual impacts on biodiversity”.

For the effects of cross-compliance on water, the picture is more complex. The scientists found that cross-compliance can be “an effective tool”, but that “its contribution to improved water status mostly depends on the standard set by member states”. However, EU countries “usually settle for minimum standards, with few of them really trying to prevent potential bad effects associated with agricultural practices”.

In addition, cross-compliance does not apply to all farmers, and not necessarily to the ones who cause the most water pollution. The main water pollutant from agriculture are nutrients (from fertiliser use and livestock manure), pesticides, sediment (from soil erosion) and faecal microbes (from livestock and manure). Nevertheless, a lot of livestock farms do not have to respect cross-compliance, and neither do the sectors that use the highest quantities of fertilisers and pesticides (flowers, fruit, vegetables and wine).

So, with all this damning evidence, surely the European Commission is rethinking how to enforce basic rules to prevent harm in the reformed CAP? They’re not. Cross-compliance is changing name (to conditionality) and there are some new rules, but some rules were removed, it will still not apply to all farmers, and it will still be up to member states to set the detailed standards.

What would be a better system? If we think outside the CAP box and look at how environmental harm is prevented in other sectors, the obvious answer is that setting those basic rules through regular regulations would certainly be more effective, fairer (everyone playing by the same rules, in and out of the CAP) and cheaper. If we must remain within the CAP box, then let’s set minimum standards at EU level to stop this destructive race to the bottom, and let’s improve enforcement, with higher penalties for (intentional) non-compliance.

5. Direct payments are doing more environmental harm than good

Direct payments are subsidies that directly boost farmers’ incomes. They come in two main forms: ‘Coupled Support’ which pays farmers per unit of product, and the ‘Basic Payments’ which are the main form of income support, paying farmers a fixed amount per hectare of land they farm. This is where roughly 70% of the CAP budget goes, or more than €40 billion per year.

Environmental NGOs have criticised both forms of direct payments for decades, as they are known to incentivise environmentally harmful intensive agriculture. This criticism has been echoed by countless scientists and economists. To name but one example, Harald Grethe, an advisor to the German government, presented a compelling critique of Basic Payments in a hearing at the European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee last year.

Despite making up the bulk of the CAP budget, direct payments, on the whole, adversely affect water and biodiversity because they go mainly to more intensive farms. This is why environmental NGOs, economists such as Prof Grethe, and small farmers alike have been asking to phase them out in the new CAP. Instead, the CAP budget should be used to incentivise and reward farmers to adopt or maintain nature and climate-friendly farming practices.

6. “Greening” is not working

“Greening” is a set of three rules that (most) farmers receiving direct payments need to comply with to get the final 30% of their payments. These are crop diversification, maintaining permanent grassland, and dedicating 5% of arable land to Ecological Focus Areas (EFA).

A previous study of greening’s effectiveness by the same authors found that greening measures had only led to small changes in management practices and consequently had limited environmental and climate impacts. These studies confirm those older findings.

Diversifying crops grown on a given farm is generally beneficial, but considering that it was adopted as an alternative to the much more important practice of rotating crops from year to year, its impact is far from what it should be. In addition, an “equivalence scheme” won by reluctant agricultural ministers during the last reform, which exempts maize monocultures in France from this requirement, is found to have negative impacts on water quality and quantity, as well as on biodiversity.

The Ecological Focus Areas are areas which are meant to be dedicated to biodiversity, such as hedges, flower strips or fallow land. However, additional options were added by unwilling CAP decision-makers during the reform: catch crops and leguminous crops. While both are good crops as part of general land management, they “tend to be of low biodiversity value”. Yet, the below graph by CAP expert Sebastian Lakner shows clearly that EU countries overwhelmingly favoured less effective options.

So how will the new CAP learn from the lessons of Greening? If you ask MEPs in the European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee and EU agriculture mInisters: it will not. Both groups have been trying to repeat history on two counts. First, by turning the new “Eco-schemes” proposed by the Commission (a measure which is meant to pay for specific farming practices benefiting the environment or climate) into a sort of “Greening 2.0”.

Second, by keeping the weaknesses of current greening in place: allowing leguminous crops grown in “EFAs”, replacing crop rotation with diversification, and allowing ineffective “equivalence schemes” again.

MEPs in the Parliament’s Environment Committee were better inspired, and set a minimum four-year length for the crop rotation rule (a win-win-win for all environmental dimensions), and added a minimum percentage of 7% for “EFAs”. This is exactly the way we need to go.

7. Some subsidised investments in irrigation exacerbate water pressures

The study found clear evidence of negative impacts on water resources caused by investments in irrigation supported by the CAP. This was possible due to weak rules and derogations. Water over-abstraction, compounded by climate change, threatens the survival of agriculture itself in parts of Europe. So the new CAP must become better at addressing quantitative water issues, notably by promoting water savings.

How? Support for irrigation systems should be limited to the improvement of existing installations with effective water savings, verified afterwards. The creation of new irrigation systems should not be supported in areas where water bodies are stressed, unless the overall project involves a less water-dependent farming system (e.g. agroforestry, drought-resistant crops, shade nets, etc.).

8. Some measures do work, but at too small a scale to make a real impact

The Agri-Environment-Climate Measures (AECM) and Natura 2000 measures were found to be beneficial to biodiversity and water – in the case of biodiversity, thanks to “significant contributions to the conservation, and to a lesser extent restoration, of semi-natural farmland habitats and their species”. In addition, “there is good evidence that organic farming generally provides biodiversity benefits, particularly where it occurs in more intensively farmed landscapes.” So are these measures used widely to address pressing environmental challenges?

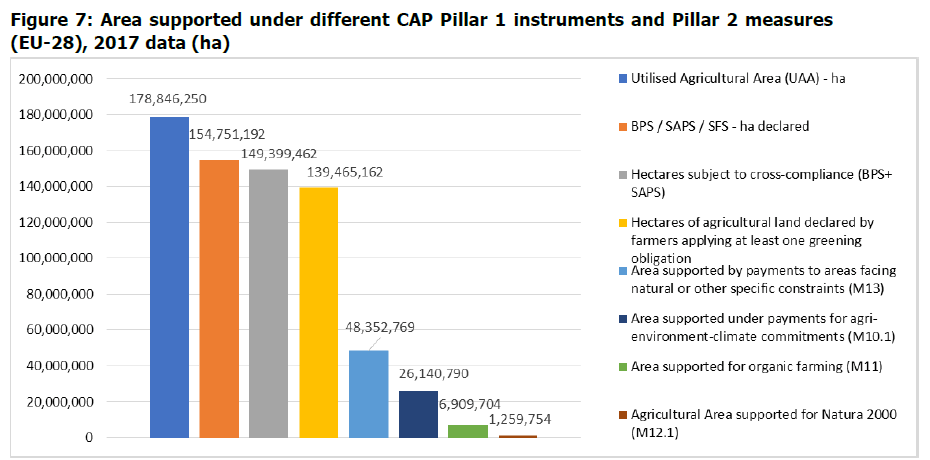

Like most businesses, farmers go where the money goes. As 70% of the CAP budget is absorbed by Direct Payments, very little remains for targeted measures, and so uptake is very low. A picture speaks a thousand words: in the graph below, the smallest three bars are the most effective measures in the CAP for biodiversity and water protection:

The new Commission has committed itself to promoting organic farming in its Farm to Fork Strategy. This is welcome, but will require sufficient funding to make it happen. When it comes to AECM and Natura 2000 payments, the new CAP must ensure these measures are massively upscaled in the next decade.

So where does this leave us, and where next?

For roughly half of the EU’s surface water and a quarter of groundwater bodies which are failing to achieve good status because of agricultural pressures, the study concludes that “the effects of the studied instruments are not sufficient presently to reverse the situation.” Similarly, “the combined effects of the CAP have not been sufficient to counteract the pressures on biodiversity from agriculture both in semi-natural habitats and in more intensively management farmland.”

It’s not too late for the new CAP, which is being reformed now, to do better. But there is one fundamental flaw in the draft new CAP, that this study highlights time and time again: if the CAP doesn’t achieve good results, it will be down to the choices made by member states. That’s where alarm bells go off. In the proposed new CAP, the Commission is giving national governments more flexibility in how they will implement the CAP. They will also be expected to justify their choices, but will that be enough? Will they have the necessary will to make some hard choices, which they have so far not had?

Our precious soil, water, biodiversity, and climate can’t afford to lose this bet. That’s why we are calling on MEPs to use their powers to strengthen the environmental safeguards, set common quantified objectives, enhance the role of environmental authorities and stakeholders in CAP implementation, and allocate sufficient funds to measures that incentivise and reward farmers to adopt agroecological practices. There is no Planet B, so the CAP must become a force for good so that EU farming works with nature, protects our finite soil and water resources, and helps solve the climate crisis.