New proposal to regulate waste shipments mitigates the consequences of EU trash exports, but fails to address the scale and impact of waste trade, writes Roberta Arbinolo.

The proposal for a revised EU Waste Shipment Regulation was tabled yesterday by the European Commission. NGOs welcome the text a step forward, but demand a stronger ban on waste exports, a better alignment with the EU waste treatment hierarchy and fairer shipments for reuse.

Shipping the problem out

Shipping waste abroad is a widespread practice that allows EU governments to export the true costs of proper waste management to third countries, often in lower-income countries.

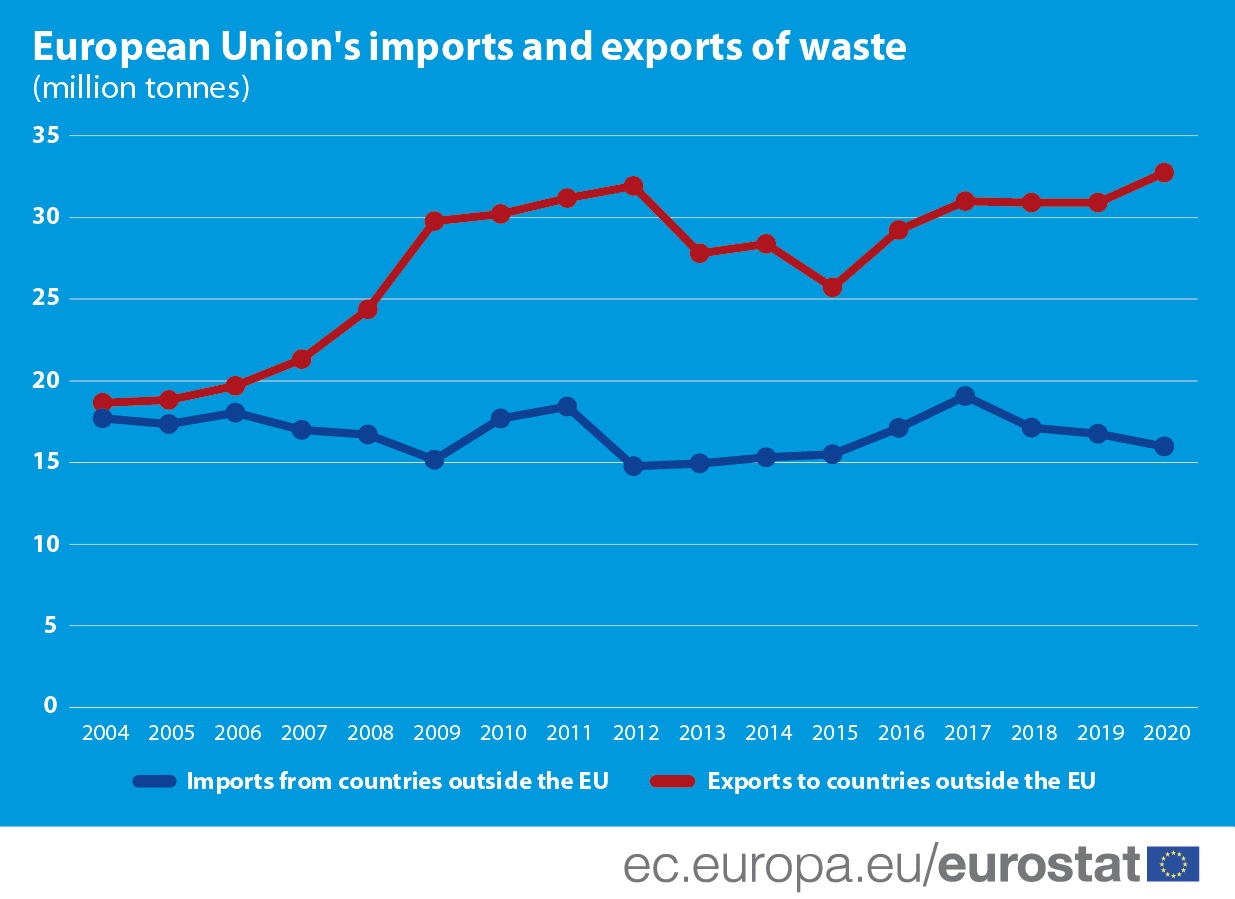

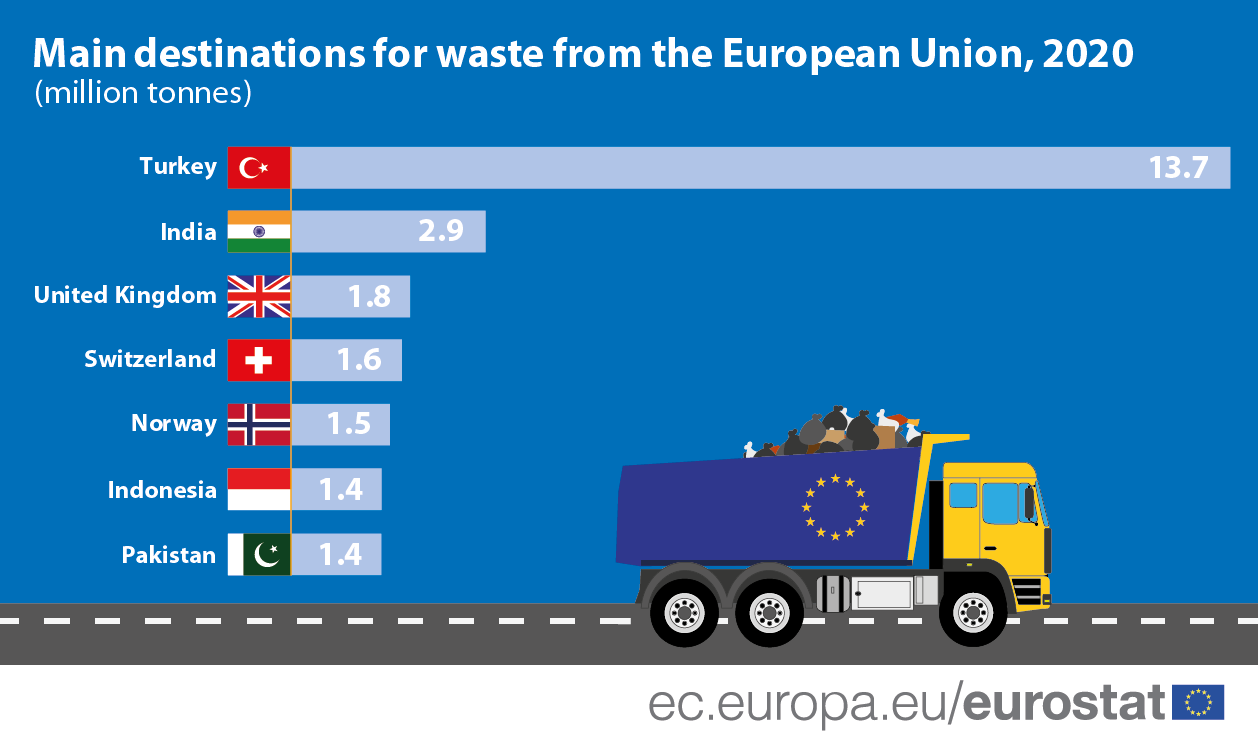

In 2020, EU exports of waste to non-EU countries reached 32.7 million tonnes, an increase of three quarters (+75%) since 2004. The largest share of this waste was sent to Turkey (13.7 million tonnes), followed by India (2.9 million tonnes), the UK (1.8 million tonnes), and Switzerland (1.6 million tonnes), Norway (1.5 million tonnes), Indonesia and Pakistan (1.4 million tonnes).

The European Environmental Bureau, the Rethink Plastic alliance and the Break Free From Plastic movement have repeatedly urged the Commission to intervene and halt the significant health, environmental and social burden of EU waste, notably plastics, on receiving countries where treatment infrastructures are often already overwhelmed.

Hazardous waste exports mostly remain within the EU: in 2018, 7.0 million tonnes of the hazardous waste exports from EU Member States were shipped to another member state, corresponding to approximately 91% of the total exports.

The new regulation proposed by the European Commission aims to bring EU waste shipment policy more in line with the waste treatment hierarchy and sound environmental waste management, two guiding principles of EU waste policy. However, NGOs highlight that derogations and loopholes risk watering it down.

Tighten the ban

The text includes a ban on waste exports to non-OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries, and may therefore temporarily divert waste exports to OECD countries only, but it will not make it harder to export waste, and it will not ensure that valuable resources remain in the system within the EU.

Green NGOs advocate for a strict ban, which would be easier to enforce and would create additional pressure to cut waste generation and virgin resource consumption in the EU.

Stéphane Arditi, Director of Policy Integration and Circular Economy at the EEB, told META:

“Shipping waste outside the EU is not only an unfair delegation of our duty to manage our own waste and an obstacle to waste prevention. It is also a missed opportunity to turn waste into secondary raw materials, reducing our dependence on imported natural resources and eventually making the EU a secondary raw material exporter.”

NGOs also stress the significant potential for illegal plastic waste trade practices to continue under current proposed measures, which fail to fully address current legislative or implementation weaknesses.

Tim Grabiel, Senior Lawyer at the Environmental Investigation Agency, commented:

“This proposal gets some things very right and some things very wrong. While we commend the Commission for continuing to take action to limit plastic waste exports to non-OECD countries and enhance independent monitoring, the lack of consent procedures on plastic waste movements within the EU will create new dumping grounds and exacerbate illegal trade.”

Follow the hierarchy

Exports for waste disposal are prohibited by default, within or outside the EU, but the text seems to miss a distinction between shipments for reuse and recycling, and shipments for lower forms of recovery, such as incineration.

This makes it as easy to export materials to another EU or OECD country for incineration as for reuse or recycling – at odds with the EU waste hierarchy recommending to prevent, reuse and recycle before considering incineration as an option.

Fix shipping for reuse

The proposal also makes a distinction between shipments for reuse and shipments of waste, but neglects the fact that products shipped for reuse will at some point reach their end of life and need to be managed in the receiving country.

For items such as electronics and possibly textiles and cars in the future, consumers pay so-called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) fees to support correct collection, recycling and waste disposal. However, if the fees paid by consumers in the EU do not follow the products when they are shipped elsewhere for reuse, they will unduly remain with producers in the exporting countries, instead of helping receiving countries manage the waste treatment stage.

Time to steady the ship

Over the next 12 to 18 months, the Waste Shipment Regulation proposal will be discussed by the Environment Committee of the European Parliament as well as with member states’ representatives within the Council.

“The Commission’s proposal is a step in the right direction and, if strengthened, could lead to the most ambitious legislative piece on plastic waste trade in the world”, said Pierre Condamine, Waste Trade Policy Officer at Zero Waste Europe.

“It is now in the hands of the European Parliament and EU countries to increase the ambition of the proposal and make it fit for the challenge it seeks to address.”